It was August, 1903 and Kruger National Park game

ranger Harry Wolhuter was returning from a

horse patrol accompanied by six black game guards, a string of donkeys carrying

camping equipment and supplies and three “Boer” dogs that guarded the camp at night. The water hole they arrived

at was dry and, as it was late in the afternoon, Wolhuter decided to ride ahead to the next water hole, accompanied by Bull, one of the dogs.

Darkness descended quickly and soon he was following the rough trail dimly illuminated by a canopy of stars. As he rode along, he heard something

running in the grass nearby

and assumed it

was a reedbuck, common to the area. Suddenly,

he realized that the noises in the grass were being

made by two lions running alongside his horse.

Knowing they intended

to attack his horse, he dug in his spurs and made a valiant

attempt to escape,

but the lions were too close.

As his horse responded to his spurring, he felt an enormous blow on his back as one of the lions jumped up onto

the horse’s hindquarters. The frantic bucking of his mount dislodged

the lion, but also sent Wolhuter

flying out of the saddle and onto the back of the second lion running alongside. This animal immediately grabbed him by his right shoulder

and began dragging

him towards a nearby patch of bush where, presumably, the lion planned

to dispatch and eat its prey! As he was pulled along with his face pressed into the mane of the lion and the back of his legs dragging along the ground, Wolhuter

tried digging in his spurs to slow the lion’s progress.

However, this only angered the lion,

which shifted its grip on his shoulder adding to his extreme agony. He tried calling out to Bull but realized that his dog had probably

followed the escaping horse, not aware that he was no longer on it.

As the slow progress

towards a certain and painful death continued, Wolhuter

remembered the sheath

knife on his belt. He was not very hopeful

that it might still be in the sheath, as it had often fallen out on less strenuous

occasions. He manoeuvred his left hand around his back and was relieved

to find the knife still

in its sheath. He carefully pulled the knife out and began

to consider whether he would be able to reach a vital spot on the lion. He felt carefully along the animals

shoulder and stabbed

it twice where he thought the heart to be.

The lion let out a roar and released its hold on Wolhuter,

who immediately stabbed it again in the throat. Judging

from the gush of blood,

he believed he had severed

its jugular vein.

To his intense

relief, he heard the lion move off through the grass and, despite

the pain in his shoulder, managed

to get to his feet. Unsure as to whether

he had seriously wounded the animal and fearful of the return

of the second lion, he looked about for a tree that he could climb using only his left arm. After a few attempts, he managed to find a suitable tree which had a fork in its branches about three metres off the ground.

Securing himself to the trunk

with his belt in case he lost consciousness, Wolhuter realized

that a determined lion could probably climb high enough to get at him, but his growing weakness

from loss of blood ruled out any further attempts

to find another tree. Resigned

to stay where he was, Wolhuter

struggled to remain

conscious so he could listen for the arrival of his patrol and warn them of the presence

of the lions.

From his perch in the tree, Wolhuter could hear the struggles of the wounded lion and what he

thought was its death moan. However, his relief was short-lived as he became

aware of the return of the second lion. It did not take this lion long to discover

Wolhuter in his refuge

and, on reaching the base of the tree, it reared up against the trunk and began to climb up. To Wolhuter’s intense relief, his dog Bull rushed out of the darkness barking furiously at the lion,

which broke off its attempt to reach him and, instead, tried to catch the dog.

Each time the lion tried to climb the tree, the dog’s frantic barking distracted it to the point where it eventually withdrew a short distance, probably hoping Wolhuter would climb down from the tree.

Each time the lion tried to climb the tree, the dog’s frantic barking distracted it to the point where it eventually withdrew a short distance, probably hoping Wolhuter would climb down from the tree.

Wolhuter knew better than that and his patience was rewarded by the sounds

of the approaching patrol. At his shouted warning,

they fired off a few shots to drive off the lion and soon had a large fire burning. As they were desperately short of water, Wolhuter

decided they would

continue on to the next water

hole, where he knew his game guards

could wash and

dress his wounds.

The march to the water hole was agonizing for Wolhuter

and made even more fearful when the patrol realized

that the second lion was following them. Fortunately, Bull and the other two dogs were able to keep him at bay.

Wolhuter knew better than that and his patience was rewarded by the sounds

of the approaching patrol. At his shouted warning,

they fired off a few shots to drive off the lion and soon had a large fire burning. As they were desperately short of water, Wolhuter

decided they would

continue on to the next water

hole, where he knew his game guards

could wash and

dress his wounds.

The march to the water hole was agonizing for Wolhuter

and made even more fearful when the patrol realized

that the second lion was following them. Fortunately, Bull and the other two dogs were able to keep him at bay.

The next morning, Wolhuter sent two game guards back to the scene of the attack to look for his rifle and the dead lion. They returned having found his horse and rifle, together with the skin, skull and heart of the lion to show him where his knife had penetrated the organ.

Now unable to walk, Wolhuter

had his game guards make a litter from poles and blankets and the patrol set out on the five-day march to the nearest medical

help at Komatipoort. The wounds soon turned septic and Wolhuter, in great pain and with a raging fever, lapsed in and out

of consciousness. The doctor

at Komatipoort, who lacked the medical

facilities that Wolhuter required,

sent him by train to Barberton

Hospital. However, even there, doctors

did not hold out much hope for his survival.

Fortunately, they had not

taken into account the incredible toughness

of the man and his will to live. Within two months of the attack, Harry

Wolhuter was back at work in his beloved

Kruger National Park.

The Lindanda memorial

is a series of stone

tablets marking

the locations of the initial

attack by the lions, the place where Wolhuter

was seized by the

first lion and, set in a concrete

cairn, the skeletal remains

of the actual tree he climbed to escape the second lion. Visitors

stopping at the memorial site are not allowed to get out of their cars. However, I don’t think that anyone,

once having read the description of the attack

on the various tablets, would

feel like leaving the safety of their car.

The Lindanda memorial

is a series of stone

tablets marking

the locations of the initial

attack by the lions, the place where Wolhuter

was seized by the

first lion and, set in a concrete

cairn, the skeletal remains

of the actual tree he climbed to escape the second lion. Visitors

stopping at the memorial site are not allowed to get out of their cars. However, I don’t think that anyone,

once having read the description of the attack

on the various tablets, would

feel like leaving the safety of their car.

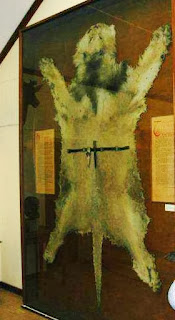

That evening, when we stopped for the night

at Skukuza rest camp, I made a point of visiting the Stevenson-Hamilton Memorial

Library. I wanted to show my

son, Brad, the wall-mounted glass

display case that contained the actual skin of the

lion and the knife that Wolhuter

used to save his life on that desperate night over 100 years ago.

The full story may be read in my 2009 book, “The

Queen’s Cowboys”, which is available on www.amazon.com/The-Queens-Cowboys-ebook/dp/B00AXAQP92.